Book reviews

My personal review of books I’ve read and thoroughly enjoyed

Click on + icons below to read book reviews

DO NOT DELETE !

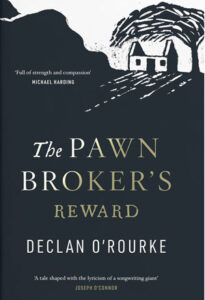

The Pawnbroker's Reward by Declan O'Rourke

Published by Gill Books, Ireland, November 2021

As soon as I read the first page of this historical novel, I was immediately transported to a period in our history that doesn’t often get spoken about. I guess it’s too painful for many, and mostly kept locked up in the dark closets of the past. But when you meet the two protagonists of this beautifully crafted novel, Cornelius Creed and Pádraig Ua Buacalla, you are drawn into their worlds and immersed into the lives of the people who inhabit this small Irish community of 1846. I loved both of them dearly. One was poor and the other wasn’t, but they were each deeply caring men with great minds and big hearts. Their only flaw was perhaps that they were somewhat misguided.

Pádraig Ua Buacalla is a young man in love with Cáit and they have two children who they dote on. He wants to carve out a life for himself and his family in the rocky outskirts of Macroom, Co. Cork but work is scarce, and, under British rule, opportunity doesn’t present itself much. Forced to depend on potatoes to sustain them because everything else was grown for export, Pádraig finds himself at the mercy of the powers-that-be when the potato crop fails for a second season in a row. All around him people are going hungry, and we already know it isn’t going to end well. Over a million people perished during this period in history, and another million fled the country, all because of food scarcity.

Declan put his heart and soul into this book. It comes through in the little details, not just in the 15 years of research that went into its creation. He has told the story truthfully and with an incredible skill that I hadn’t expected from a songwriter. He has managed to capture the essence of 19th century Ireland but with contemporary language that draws the reader in in a heart-warming way despite the incredibly brutal themes that are explored.

Pádraig is an Irish speaker from the Muskerry Gaeltacht who has little experience of speaking English. During a conversation with his fellow labourers while breaking rocks for a pittance pay, Pádraig is asked if he would consider leaving the country to join an overseas regiment. It was, after all, a way to avoid starving to death. Pádraig’s response was to quote from a poem by Eoghan Ó Súilleabháin:

Nuair a thiocfaidh an chaint don bhfiach dubh.

Nuair a thiocfaidh an míol mór ar an Moing.

Nuair a thiocfaidh an Fhrainc go Sliabh Mis.

Nuair a chaillfidh an sagart an tsaint.

Is ea a thiocfaidh an chaint don bhfiach dubh.

His friend, Denis, translated for those in the group who didn’t understand, and they gazed at Pádraig in awe as they began to understand the powerful message contained within:

When speech comes to the raven.

When the whale will come up the Maine River.

When France will come to Sliabh Mis.

When the priest will abandon his greed.

Then, speech will come to the raven.

The respect Declan has shown towards the language of the region gives the novel depth and credibility. Pádraig’s unique voice is rich in Irish culture that is often forgotten amidst the British culture that sought to dominate our country at the time.

Cornelius Creed is a pawnbroker from a well-to-do background who also acts as a correspondent for The Cork Examiner. He has a wonderful way with words which comes through in the voice Declan employs when telling Creed’s story.

It was as if the silence was the tree itself, whose leaves, like tiny hands, trembled and conducted the ripples of a mute breeze.

Through the eyes of Cornelius Creed, we get an insight into the characters who were involved in the decision-making that would ultimately impact on the fate of the impoverished people in and around Macroom. Creed had been appointed as correspondent for The Cork Examiner to report on the meetings held by The Poor Law Guardians of the Macroom Union Workhouse. It’s at these meetings that we get to gasp at ‘the moral repugnance’ of some of its members who lack responsibility to anyone or anything other than themselves and their own interests. We see this play out in how the poor are treated when seeking relief from hunger. ‘Inmates are to be worse fed, worse clothed, and worse accommodated than that of the lowest peasant outside the walls of the workhouse.’ Such was the prevailing ethos of the Poor Law Commission. In return for nourishment, any able-bodied pauper capable of manual labour was to be employed for at least ten hours per day.

Creed struggles with the contradictions he witnesses at the meetings of the Relief Committee. He expresses his outrage in the regular letters he writes to The Cork Examiner. An example of this was sparked when a local church rector, a Mr Swanzy, had the gall to request a pay-rise for his services as chaplain of the poorhouse ‘under such incredibly stricken circumstances as those of the present was an abhorrence and something the people of the parish, nay, the people of Cork, Dublin and even London (all of whom the readership of The Cork Examiner served to inform) ought to be made aware of.’

In a letter printed in the December 1st edition of The Cork Examiner we see this playing out again when Creed reports the deplorable behaviour of Massy Warren at one of the emergency relief meetings. We begin to see Creed’s indignance building after many months of witnessing the injustices served at those meetings. ‘I should be extremely sorry’, he stated in his letter, ‘to hold that a man’s worth is to be measured by the magnitude of his purse or the chance of birth, and should much prefer the doctrine inculcated by the immortal Livy –

Qui sis, non unde natus sis, repute.

Consider what you are, not where you were born.’

But Creed turns this abhorrence inwards when he later battles to reconcile his own profiting from his customers’ misfortune. It is at this point we see the cracks appearing in Creed’s mental well-being. A man of his word and of strong conscience, he is struggling to contend with the attitudes and greed of the rich while trying to reconcile his own role as a pawnbroker. He comes face-to-face with the truth when his brother-in-law accuses him of double standards ‘Doing good for the poor on one hand and charging interest with the other.’ We watch Cornelius sink into despair as he begins to question his existence, and tells his sister ‘I’ve been very conflicted… For quite a while there I had myself convinced that I could so some good. I’m a hypocrite.’ It’s almost unbearable to see this empath come to the realisation that he has failed himself and others. He tells his wife towards the end of the book that he had never intended for his pawnbroker business to be anything other than ‘a leisure interest. A trickle of income on the side. Small amounts.’. He hadn’t anticipated that hordes of people would trek into Macroom to swap the coat off their back or the blanket off their bed in exchange for enough money to feed their children for a day, a week…until relief came.

Meanwhile, Pádraig returns home empty-handed and downtrodden to his starving wife and children after working himself to the bone and missing out on payment because of some bureaucratic codswallop that has prevented the men from being able to feed their families on Christmas day. We feel his overwhelming hopelessness at the way things are unfolding.

There’s mention of The Honourable William White Hedges, resident Lord of the Soil, owner of the town, and of Macroom Castle, where he actually resided when he was not in absentia.

It was a disgrace, Creed mused, that ‘the man with the most power to effect the events of the district had the least interest in doing so.’ It’s hard not to feel deep indignation for the injustices and hardship endured by the people under the supposed auspices of the so-called Lord of the Soil.

Pádraig joined the long queues of men who turned up day after day in the hope of getting work with the emergency labour programme facilitated by the Relief Committee. When he got turned away, his only option was to make the daily 13-mile return journey barefoot to the workhouse to get one meal for himself and half a meal for his little son, Diarmuidín whom he carried on his shoulders. He observed the hundreds of men competing for the handful of labouring jobs, all equally desperate to find the means to feed their families. And to think that the arrogant rich of the time sought to blame these men for their own misfortune as we witness in a scene where the morally repugnant Massy Warren is enjoying his lavish Christmas lunch while observing ‘How poor do they have to be before they decide to do something about it?’

Pádraig saw it as proof when so many men turned up looking for work that they were not intentionally idle. He couldn’t help but notice that ‘resignation and indifference has lately come to characterise the expression of many of those who had been struggling for a protracted period.’ He knew that he had to keep on pushing if he was to survive.

This book has been beautifully and skillfully written, yet it is at times a difficult read. I found a fire burning in my belly and a tugging at my heartstrings the more I learnt about the conditions of those harrowing times. And there were tears. It did however fill me with a renewed sense of appreciation for the abundant times we now live in and serves as a good reminder of the atrocities our ancestors had to endure. If anything, this book will awaken us all to the fact that profit should never be considered more important than our shared humanity.

This book should be on everyone’s reading list this Christmas for all the reasons I mentioned. Order your copy today from www.bookdepository.com. You won’t regret it!

The story behind the book

Watch the interview I did with Declan where we talk about what inspired him to write this book.